Key Takeaways of this Article:

✅ Why flexible automated production systems are needed?

✅ How production can be automated with fenced-in and fenceless robots?

✅ What human-robot-collaboration is and which levels of interaction are possible?

Motivation for Flexible Automation 🚀

People love to customize their products: whether it is configuring the upholstery and trim of your new sedan interior, individualizing your home decor or customizing jewelry and accessories for your personal style. Product customization satisfies the desire to have a unique product that is crafted to meet your individual preferences. Products become more individual and less standard. As a result, a high variety of a workpieces (high-mix) at a reduced number of the exact same workpiece (low-volume) needs to be produced: the so-called high-mix-low-volume production. This trend is characterized by demand variations, short product iteration and increased product personalization.

All this individuality comes at a price: it has to be compensated by modern manufacturing systems, that shift their production strategy from classical mass production to mass customization. Producers are confronted with a variety of challenges and tension fields, such as:

- 🚚 Maintaining high quality while guaranteeing short delivery time

- ↗️ Need for flexible and agile production processes

- 📈 Continuous improvement, optimization and profitability

- 👨🏼 Rising need for higher skilled labor

- 👨🏼 Experiencing skilled labor shortage and growing staff turnover.

To tackle these challenges, the Industrie 4.0 framework provides a toolset of different technologies, that satisfy the need for flexible and production systems. One of these are collaborative and fenceless robots, that can be integrated into existing brownfield production environments without the need for static fencing. This vision of fenceless automated manufacturing is linked to explicit expectations, such as:

- ⏱️Cycle time improvements: the no. 1 automation reason that is directly linked to the Return of Investment (ROI) and economic advantageousness of an automation solution

- 💰Cost savings: reduce the investment cost since no safety fence is required

- 🔲 Space savings: reduce the footprint since no safety fence is required

- ⚠️ Guaranteeing occupational safety: ensure safe operation next to the robot without a safety fence

- 📱 Higher flexibility due to easy programming: reduce reprogramming time with new easy programming methods, such as robot hand guiding

The Conceptual Progression of Fenceless Systems 📈

To meet these requirements, different automation technologies have emerged to improve productivity while providing sufficient flexibility for workpiece variations. Besides classic automation solutions, that were often too rigid, robots became the most flexible solution.

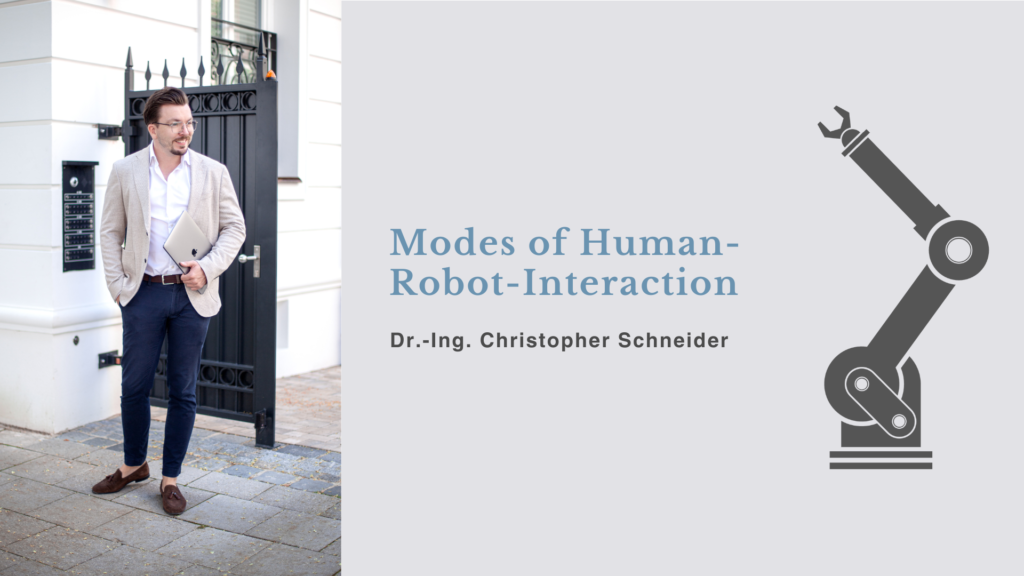

There are different ways to operate a machine and run production. From classical manual execution over the use of robots behind safety fences or also fenceless robots. The different options are explained as follows.

👨🏻🔧 Manual Execution

Traditionally, tooling machines are operated manually. The complete process of setup & tooling, loading and unloading the machine is done entirely by the operator, which provides high flexibility especially for small to middle lot sizes. Due to the idle times during processing, high lot sizes become less profitable.

🦾 Fenced-In Industrial Robot

To grant a greater productivity for large lot sizes, industrial robots are used for the loading and unloading of the machine. This provides maximum productivity since the automated work cell can operate autonomously and produce workpieces in one, two or three-shift operation – completely scalable. The downside is the requirement for an automated process chain: from material in-feed over setup and tooling to material out-feed – everything needs to be designed in a robot-friendly way. This limits the flexibility, especially for changing workpieces. Additionally, the issue of unproductive idle times is still present, since the robot waits for the next workpiece during processing. By incorporating further value-adding processes, such as deburring or quality inspection, these time slots can be utilized.

To guarantee occupational safety of such an automated cell, industrial robots have been isolated behind a robust safety fence for physical separation from the operator. Safety doors grant safe access to the robot and shut the robot down as they are opened, e.g. during maintenance or error handling. Safety fences are an easy safeguarding option with a small footprint and an effective shielding from the robot itself but also from potentially flying objects. The static installation, however, limits the possibilities for factory transformation, logistic design and human-robot-interaction.

🦾 Fenceless Industrial Robot

For a better compromise between productivity and flexibility, industrial robots have been taken out of their fence. By using external safety devices, such as laser scanners, industrial robots can be operated fenceless or with only partial fencing. In such a system, the robot operates at full-speed when nobody is present and decelerates the operating speed with increasing proximity to the operator until the human is too close and the robot stops. Opening the work cell grants access to the robot and to the machine, allowing the operator to do tooling and setup operations manually. Especially for middle to large lot sizes, where the tooling needs to be adjusted for changing workpieces, this manual setup comes handy since it provides the required workpiece flexibility. The monotonous loading and unloading of the machine is delegated to the robot in a completely automated way. This combination of human and robot provides a well-balanced compromise between productivity and flexibility.

🦾 Fenceless Collaborative Robot (Cobot)

The next evolution stage of fenceless robot systems are so-called collaborative robots (cobots). Instead of using robot-external safety devices for fenceless operation, cobots have integrated sensor technology, that detects external contact forces (i.e. with the operator) which trigger a safe stop of the robot. This new robot technology enables human operations close to the machine and robot, such as refilling raw material, without triggering a stop of the robot (like for the fenceless industrial robot). Similar to the fenceless industrial robot system, loading and unloading of the machine is automated by the robot, while setup and tooling operations are done manually, providing similar benefits in productivity and flexibility as the previous system.

Levels of Human-Robot-Interaction (HRI) 🤖

To realize the previously mentioned fenceless robotic automation solutions, different forms of human-robot-collaboration (HRC) or rather human-robot-interaction (HRI) are available.

According to ISO 10218-1, a collaborative application is defined as a

“state in which [a] purposely designed robot work in direct cooperation with a human within a defined workspace”.

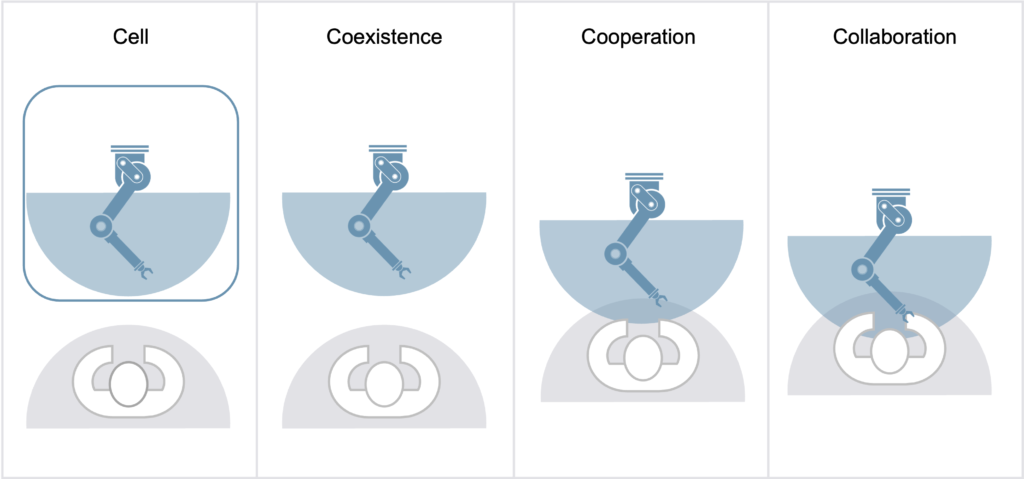

In most cases, a real collaboration between operator and robot does not occur. Other HRI forms, like coexistence or cooperation, are suitable alternatives for fenceless operation. To include all forms of fenceless operation, the narrow term “human-robot-collaboration” should be extended to “human-robot-interaction”. The following topology subdivides different levels of human-robot-interaction, which are explained as follows.

1️⃣🔲🦾 Cell

This is the classic robot cell for a fully-automated station. A fence separates the robot safely from the operator. In this case, there is no interaction between operator and robot at all during operation.

2️⃣🦾👋 Coexistence

In coexistent workstations, robot and operator work without spatial separation next to each other but without or only limited interaction. Human and robot do not share a mutual workspace.

3️⃣🦾👋 Cooperation

In the middle between coexistence and collaboration there is cooperation. In such workstations, robot and operator have a mutual workspace in which they can also work at the same time.

4️⃣🦾👋 Collaboration

Collaboration implies direct interaction between human and robot, that means that both interaction partners share a workspace in which they are working at the same time at the same workpiece together.

References

Schneider, Christopher (2022): Robotic Automation of Turning Machines in Fenceless Production: A Planning Toolset for Economic-based Selection Optimization between Collaborative and Classical Industrial Robots, Doctoral Thesis, Technische Universität Chemnitz.

Winkelhake, Uwe (2017): The Digital Transformation of the Automotive Industry: Catalysts, Roadmap, Practice, Springer.

Bauer, Wilhelm/Manfred Bender/Martin Braun/Martin Braun/Peter Rally/Oliver Scholtz (2015): Lightweight robots in manual assembly – Lightweight robots open up new possibilities for work design in today’s manual assembly, Fraunhofer IAO.

Dispan, Jürgen (2017): Entwicklungstrends im Werkzeugmaschinenbau 2017: Kurzstudie zu Branchentrends auf Basis einer Literaturrecherche, Hans Böckler Stiftung.

Blecker, Thorsten/Gerhard Friedrich (2006b): Mass Customization: Challenges and Solutions.

Khojasteh, Yacob (2017): Production Management: Advanced Models, Tools, and Applications for Pull Systems.

Autodesk/Kuka (2023): Deciphering Industry 4.0 Part III: Smart Logistics and Mass Customization.

Kuka (2022): Ihre Produktivität gesteigert – Automation für Werkzeugmaschinen.

Zaeh, M. F./M. Ostgathe/F. Geiger/G. Reinhart (2011): Adaptive Job Control in the Cognitive Factory, in: Springer eBooks, S. 10–17.

Makris, Sotiris (2021): Cooperating Robots for Flexible Manufacturing, Springer series in advanced manufacturing-

International Organization for Standardization (2011): ISO 10218-1: Robots and robotic devices – Safety requirements for industrial robots – Part 1: Robots.

Onnasch, Linda/Xenia Maier/Thomas Jürgensohn/baua: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin (2016): Mensch-Roboter-Interaktion – Eine Taxonomie für alle Anwendungsfälle.